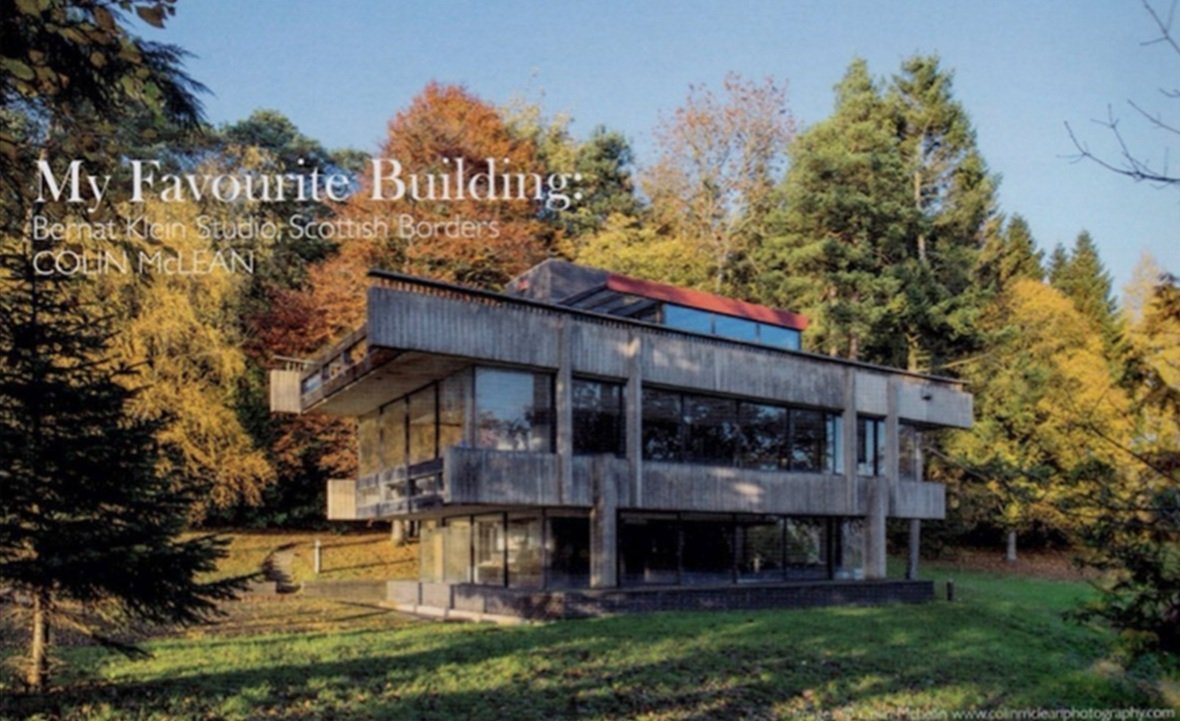

The Klein Studio

Designed by Peter Womersley in 1972 for Bernat Klein, photo © Michael Smith, 2016

James Colledge, a founding member of Preserving Womersley, considers its current state and, by stepping back in time, a different future.

The Financial Times Industrial Architecture Award 1972 commended the Klein Studio, which was described thus:

'This building, in essence a delicate table of concrete with glazed sides beneath two tiers of overhanging shelves, stands in a grove of trees which - as the architect no doubt intended - complement its proportions and style. The detailing, both inside and outside, is restrained and immaculate which is of more than usual importance in a structure which invites those outside to look into, and through it, from every angle. The area is remote and scenically distinguished, and the successful placing in it of this sophisticated building, which makes no concessions to regional taste, places feathers in several caps, including that of the local planning authority.'

Peter Womersley and Bernat Klein - the friendship that has given a priceless cultural legacy to the Scottish Borders.

From the moment Bernat and Margaret Klein spotted Farnley Hey in Yorkshire; through to the realisation in 1958 of High Sunderland, the beloved Klein family home that brings to mind the Barcelona Pavilion of Mies van der Rohe; to 1972, with the completion of the acclaimed Klein Studio and its references to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Falling Water, that chance encounter led to the blooming of one of the most creative and influential friendships in the history of Scottish modernism.

Bernat Klein and Peter Womersley, intellectual, creative, fearless and unshakeable in their mutual respect for each others’ work, combined to leave a legacy the likes of which it is hard to imagine these days. It’s fortunate that this legacy is beginning to achieve the level of acclaim it deserves. But the legacy, in Peter Womersley’s case, is not secure: the Klein Studio, for all its innovation and acclaim, is in a parlous state. In this brief reverse history, we seek to draw a line from its current precarious state as it continues under the same ownership it has for twenty years, back to the perfect realisation of Peter Womersley’s iconic design - to return to the public imagination what was and what might yet again be.

High Sunderland, Michael Smith, 2017

Barcelona Pavilion, James Colledge, 2010

A brief walk back in time

Imagine Bernat Klein walking down from High Sunderland today, through the woods, to the Studio, something he must have done thousands of times. He would be confronted by this:

Michael Smith, 2019

It is this sight that Shelley Klein refers to in the chapter on the Studio in her recent book:

'Over the last few years of his life I tried at all costs to avoid driving Beri past The Studio, but if it was necessary to go in to Selkirk, I'd put my foot down hard on the accelerator. Beri hated seeing this once stunning building not only abandoned but allowed to deteriorate. Indeed, so affected was he that recently, while sorting through some of his books, I noticed he'd underlined the following remark by the architect Berthold Lubetkin while in conversation with Rowan Moore (architecture correspondent for the Observer) on the subject of why he hated revisiting his buildings: "' It is like seeing an old girlfriend," [Lubetkin] said, "who was beautiful, but has now become wrinkled and lost her teeth."' Next to this in the margin, Beri had scribbled the following words: 'The Studio!' In essence, the building has metamorphosed into the See-Through House's neglected twin: a hideous monster; a symbol of decay, rack and ruin.'

The See-through House: My Father in Full Colour by Shelley Klein, Chatto & Windus VINTAGE, P235

A couple of years earlier, stepping back a few paces, this is what Bernat would have seen:

James Colledge, 2016

And it was this sight, forlorn but still evocative of the lightness of this so-called brutalist structure, that was the spur needed to launch the Preserving Womersley initiative, undertaken by Michael Smith, Chris Hurst and me in late 2017.

Since its early days as a collective of three, I am pleased to say that, as well as having 350 subscribers, we have been joined by renowned Scottish photographer and current chair of the Scottish Civic Trust Colin McLean FSAScot LRPS, and Edinburgh architect Lindsay Buchan BSc(Eng) B.Arch.Hons. RIBA RIAS, who bring a touch of gravitas and professional constraint to our efforts.

In 2018, when Preserving Womersley was invited by the Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland (AHSS) to write about its formation and activities, I wrote this:

'The jewel in the Womersley crown is the category A listed Klein Studio (1972), commissioned by Bernat Klein and used for 20 years as his workplace and exhibition space. It is a structure of extraordinary lightness and harmony.'

James Colledge, 2017

Sold by Klein in 1992, it found a use first to house a project to support textile industry participation, displaced by the decline of their industry in the post-war decades. With that project closing in the late 1990s the Studio fell into disuse. In 2002, the building was placed on the Buildings at Risk register.

Sold again in 2002 into private hands, the current owner received planning permission to convert the building into two apartments, the upper one with a rooftop terrace. Work commenced and proceeded over the next few years, only to run into the dual problems of the 2008 downturn, and massive flooding due to a broken pipe left running, which destroyed much of the conversion work undertaken. Work was at that point abandoned.

The building has since then further deteriorated, taking on the air of dereliction that attracts both the interest of the architecturally curious and the disaffected. Most recently, evidence of vandalism and occasional unauthorized occupancy have confirmed this decline.”

Peter Womersley His Architecture and Art, James Colledge, AHSS Journal, Autumn 2018

Colin McLean

A few months earlier Colin McLean had also written in the AHSS Journal on his love for the Klein Studio.

'The Klein Studio sits at the roadside, just a short walking distance from High Sunderland. It uses reinforced concrete slabs and beams, but in a strictly horizontal form that cuts across the verticality of the mature trees of its surroundings - there are distinct signs of Frank Lloyd Wright's influence. In 1973 it won an RIBA Design Award and the Edinburgh Architectural Association Centenary Medal.

I first discovered the Klein Studio in the mid- I970s when, on a family trip to the Borders, my parents drew into the car park and we all said "Wow - what is that?" It would be fair to say that this was the moment that stimulated my interest in modern architecture. I have visited the building a number of times in recent years and watched its ongoing sad decline.

Although the category A listed studio has been on the Buildings At Risk Register since 2002, the statutory bodies seem to have no powers to take any action. One fears it will decline until it becomes dangerous and a Repairs or Demolition Notice is served. Demolition was the sentence for another of Womersley’s houses in the west of Scotland, whose fate was sealed by an uncaring owner and an equally uncaring planning authority. Surely there must be a better way to protect our built heritage?'

My Favourite Building: Bernat Klein Studio, Colin McLean, AHSS Journal, Spring 2018

Our imagined destination

These days, we all talk of the Klein Studio in fearful and nostalgic terms, concerned for its immediate future. So what is it about this magical structure that generates such emotion?

If we take a leap back in time to the 1970s, we will find ourselves confronted by a spectacle that encourages a sharp intake of breath, a moment of disbelief, and the dawning realisation that this is not a fantasy, but a reality, a work of art nestled harmoniously in its modest Scottish Borders site.

Arup Partners

It is easy to imagine Bernat, approaching the cantilever bridge, samples of yarn or cloth in hand - or are they bricks? For it is the perfectionism of someone who, as Shelley recounts, checked every brick in every delivery for its exact colour match, rejecting many, for use in a design that was itself the product of a perfectionist at work. Their combined talents filled this modest space with one of the most important modernist structures in Scotland.

Why should we care?

Because seen as it was intended by Peter Womersley and used by Bernat Klein, it fills the senses with wonder.

Preserving Womersley brings together the disparate threads of interest that alone might not be strong enough to draw attention to the plight of the Klein Studio. Collectively, it provides these interests with a louder voice which has the potential to inform and spread the word about the remarkable body of Peter Womersley’s work, beyond the somewhat rarefied world of academics and professionals. We are deliberately unfunded, working entirely on the premise that with a loud enough voice and a bit of hard work, we can steer this masterpiece into safe hands.

Please add your voice in support of this important endeavour by joining us today at Preserving Womersley