‘Bernat Klein’s Colour Box: How to pull on a thread’, by Frances Robertson

Bernat Klein Exhibition, V&A Dundee: Photography by Michael Wolchover

Dr Frances Robertson is an independent researcher on material cultures of drawing and design.

To me, the most inspiring aspect of the Bernat Klein Foundation (BKF) is that it ‘creates new opportunities’. Part of being open to opportunity comes from the BKF’s drive to create a sense of close, almost tactile, engagement with Klein’s legacy that helps to dissolve some of the ‘glass case’ feeling of historical collections, putting us in touch with the lived experience of makers, designers, collectors, new practitioners.

I’d like to reflect on two public engagement events in 2023 (an exhibition in Glasgow and a symposium/ exhibition in Dundee) that brought this home to me, pulled me in, and gave me a growing understanding of the BKF as an unfolding fabric of activity.

Bernat Klein Exhibition, V&A Dundee: Photography by Michael Wolchover

As an academic who had taught and researched design history, with additional sustained practical experience of dress, textiles, and fashion history I knew of Bernat Klein as a fixed, but somewhat unexamined major landmark in a myriad of other postwar examples. However, those two opportunities in 2023 changed my ideas and engaged me with people, materials, and processes, threading them into my own existing picture of design endeavour, involving me as a spectator and participant and increasingly informed about a whole range of projects such the educational awards, new creative outputs (such as short films and publications), public events and contemporary practice (including student research projects) inspired and influenced by Bernat Klein.

Bernat Klein Exhibition, Studio Pavilion. Photography by Alan Dimmick

Bernat Klein: Influence & Inspiration, Studio Pavilion, Glasgow

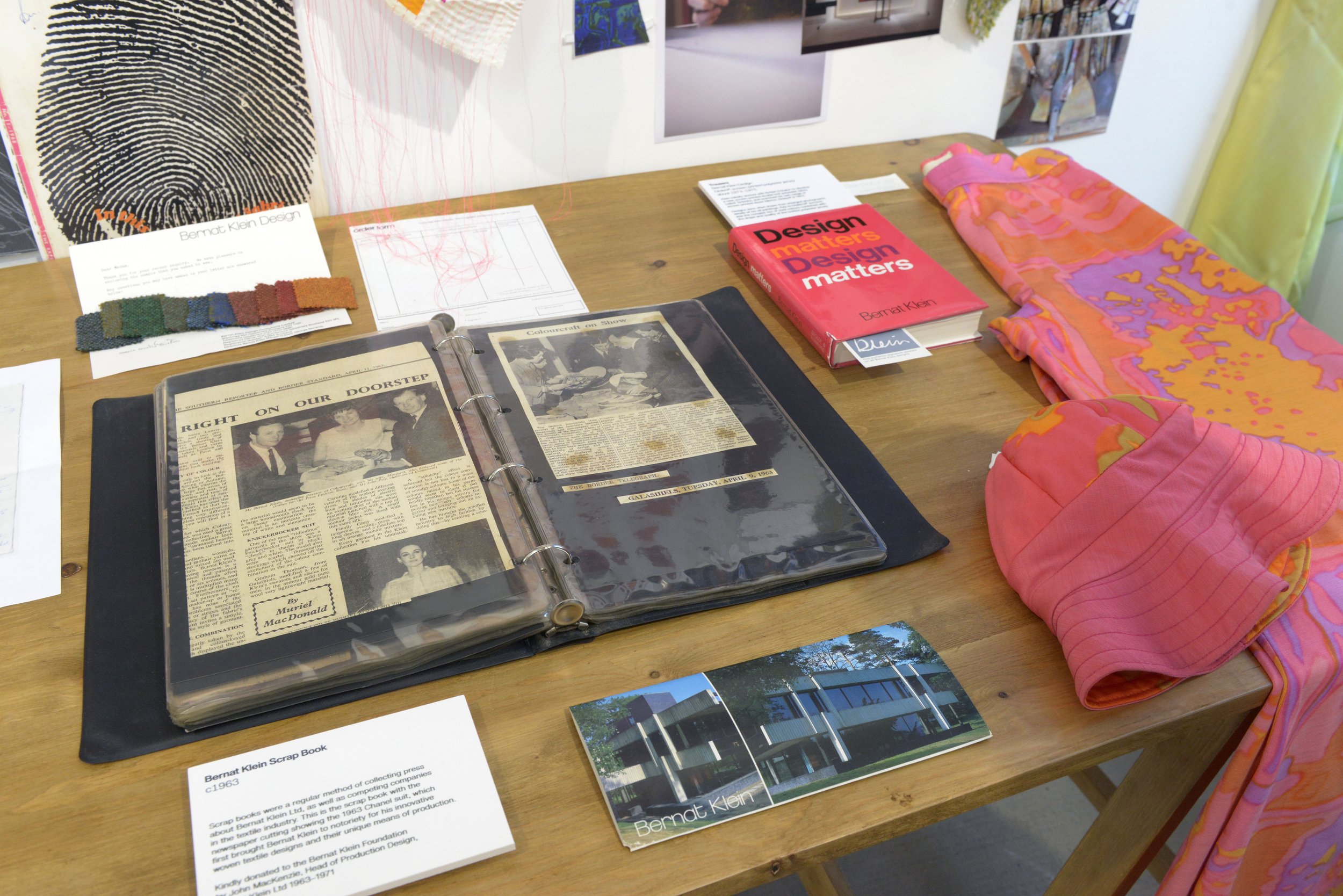

The aim of this exhibition, as explained by the curators, was to ‘showcase new ideas developed by contemporary practitioners whose work is contributing to the continuation of Bernat Klein and his legacy in design, visual arts, and architecture’. In the Studio Pavilion, new work was presented together with original examples of Klein’s design and artistic practice.

The Studio Pavilion itself is an outstanding space for creating connections and echoes within a constellation of exhibits. Although at first glance a simple airy room with large window openings on the one side to the Walled Garden at Bellahouston Park; on the other to the Courtyard space of workshops and studios, the rhythm of wall-and-window space, and the slight change in level to one side, allow one to move from one individual area to another, to concentrate fully on what is in front of you, while being able to glance back and across, making reference to other bits of information. In memory, there were several stand-out moments. The first one was the film An explosion of colour by Callum Rice (2022), filmed in the National Museums of Scotland (NMS) archives, featuring a conversation between two retired master craftsmen about their experience of working with Bernat Klein in his Galashiels textile mills c. 1960 onwards, with focus on the development of ‘space-dyed’ yarns, and the intense exploration of colour and permutations of colour and texture while working with skilled dyers and weavers. John Mackenzie, weave designer, and Keith Hendrie, dyer, opened up textile samples from the NMS collections and explained how they had been achieved.

Bernat Klein Exhibition, Studio Pavilion. Photography by Alan Dimmick

Space-dyed, or ‘random’ yarns are achieved by dipping a circular skein in quadrants into four different dye baths. At each overlap intermediate colours emerge from the interaction of dyes, creating at least sixteen discernible shades, with many intermediate and shifting areas in addition. When successful this creates a vibrant web of colour in the fabric, in which opposing or unexpected colours can lie together in pointilliste fashion. But, just as happens in bleeding together colours in a paintbox, it can also create chaotic and unpredictable muddy areas. Add to this the further random element of different kinds of yarn—fluffy, smooth, silky or, in Klein’s case, with velvet ribbon used as a warp thread, an infinite spectrum of sensory and tactile effects open up through these relatively simple starting points and permutations. It is a wonderful example of the interaction of controlled and chance elements within the bounds of skilful craft, and one of the essential challenges of weave design. The two retired craftsmen recalled with laughter several of the almost impossible demands made on the tolerance of technology during the design process, created by ‘Mr. Klein’ and his insistence on conquering and using difficult yarns full of ‘slackness’ looseness’, and ‘slubs’ in his weaves. Thus in their conversation Mackenzie and Hendrie would seize on one or another archive example in turn, remembering the process, the negotiations, the sometimes sheer obduracy of bringing together people, materials, techniques, even –in the Borders, when shuttling up and down to the Studio in later years –the surprises the weather might throw at you. The film brought forward vividly the complex forces in the field of production that need to be brought together to create a sensuous, desirable and visually arresting luxury commodity, and it conjured this information from footage skilfully gleaned by Rice from a brief, informal conversation of working memories.

Other first-hand testimonies were equally vivid in other of the short films in the show: Grainne Rice discussing her growing passion for collecting and wearing Klein garments; Lynsey Calder talking, again with close technical focus, on the process of mapping, re-printing (with different dyes onto different fabric) material in order to create faithful reproductions of some of Klein’s iconic printed polyester dresses, and thence on how that information of colours and separations were then re-translated into the different medium of digital prints, distilled into square ‘repeats’. Most importantly, the exhibition also showed actual fabric samples, that could be picked up and examined, swatches, pattern books, paintings, and printed catalogues. The presence of this breadth of material evidence, alongside photographs allowed the viewer to listen, range back and forth, and reinforce the information through all the senses.

These examples were the ones that stick in my mind, but there were other films, other exhibits and other testimonies that all planted seeds for the next stage of my immersion in the legacy of Bernat Klein: the symposium at the V&A Design Museum at Dundee.

Bernat Klein Exhibition, V&A Dundee: Photography by Michael Wolchover

Beneath the Surface: Bernat Klein, One-day Symposium in collaboration with the V&A Dundee, 1st December, 2023, 10:00 AM-4:15 PM

This symposium gathered together many different but overlapping constituencies of Klein enthusiasts encompassing collectors, design and craft practitioners (amateur and professional), academics, historians and cultural administrators. The Symposium was held in the Juniper Auditorium on the top floor of the V&A Dundee, next to the Designer in Residence Studio where a new version of the Influence and Inspiration exhibition described above was installed.

I had travelled to Dundee the day before, staying overnight, in order to immerse myself in advance in both the updated V&A permanent collection and in the Tartan exhibition and with plenty of time to walk Dundee city, with its water front and magnificent expanse of the Tay estuary and enormous skyscapes unfolding out east, west, and south from below the skirts of the man o’ war bulk of the museum building; enhanced by a severe cold snap of bright and sharp weather in Dundee and Eastern Scotland at that time.

The very fortunate coincidence of the Tartan exhibition (1 April 2023-14 January 2024 https://www.vam.ac.uk/dundee/info/tartan-inside-the-exhibition) provided a really good prelude to some of the preoccupations of the Symposium on Klein as a textile designer. Arriving late in the afternoon the day before, I found the massive Tartan galleries (filled with textiles, dress, and fashion) to be deserted apart from myself and the invigilators, giving plenty of opportunity to ponder the inexorable geometries of weave, the woollen industry in Scotland, and the daring colour combinations of tartan, allowing me, at least, to visualise Klein’s work as an enterprising excavation of a niche within this textile eco-system. Alongside these material, technical, and economic strands, the Tartan exhibition’s description of global contexts and the inclusion of recent film and artist installations also meshed in the heavy symbolic weights of the fabric, seized on by so many groups, from doting mammas, to British imperial projects of conquest and enslavement, to subcultural would-be rebels.

Arriving early next morning in a crisp blue-rose frosty morning for the Klein symposium, I passed hastily by a would-be rebel or madman standing naked in the near-freezing waters of the ornamental pool at the V&A entrance, dressed in nothing but a loud tartan plaid, sporran and bonnet, under languid observation by the Museum’s security employees. —I was unable to discover if he was a freestyle artist, a protestor, or perhaps a participant in the BBC1’s Big Weekend Experience event, scheduled in the V&A for the same day as the Symposium, but he was a striking example of the capacious discourses of tartan—official and unofficial.

The Klein groups and subgroups assembling indoors for the Symposium ‘Beneath the Surface’ were far more measured; quietly celebratory, bringing to a triumphant close the sustained period of effort since establishment in 2018 that had expanded the activities of the Bernat Klein Foundation so successfully. This essay of course only touches on two examples of the many exhibitions, workshops, publications, and research projects determinedly carried forward by BKF, largely through the efforts of many of the participants that day. I felt lucky to be included as an observer in that throng, and to hear of those outcomes so skilfully brought together. I had been reflecting on insights from the earlier exhibition at the Studio Pavilion, also reading and writing in preparation for this Symposium, for example Klein’s text Design Matters, Mary Schoeser’s writings such as Disentangling textiles and Textiles: the art of mankind, and John Gage’s writings on colour history and theory. As a result, the most striking contribution for me in the Symposium came from Mary Schoeser and her presentation ‘Bernat Klein and Émigré Designers: enriching mid-20th century British textile design’. As in the film Colour explosion and the conversation of Klein’s former skilled craft works described above, it was Schoeser’s first-hand testimony that hit home, her personal encounter with weave, weavers, and techniques during her student training and subsequent research into textiles and art history both in California and then in the UK, an account that she knit in to her moving and elegant discussion of the contribution of émigré designers to textile industry and innovation in the post-war period in the UK such as Klein himself and others such as Tibor Reich, Nicholas Sekers and Zika and Lida Ascher. In the afternoon of the same day, I admired the ‘project brief’ delivery by Jane Keith and Alison Harley of the forthcoming Bernat Klein Foundation Award which this year (2024) will invite Year 3 Textile Design students at Duncan of Jordanstone’s College of Art & Design, launched at the Symposium and involving close study of Klein’s legacy in the Influence and Inspiration exhibition at the V&A; also through close engagement with the remainder of the V&A Dundee collections as a stimulus to design development.

Thanks to these two events in Glasgow and Dundee, I revisited and thought through further sources such as Klein’s own text Eye for colour, alongside Shelley Klein’s extremely moving memoir The see-through house: my father in full colour, while working my way through more technical guides such as Ken Ponting’s A dictionary of dyes and dyeing. Overall, these encounters inspired me through the skillful curation of first-hand experiences past and present in the BKF projects of research and engagement, and the selection of telling coincidences of personal experience and examples of painstaking testing of craft and technique to build on Klein’s legacy for the future. From Shelley Klein’s The see-through house, I gleaned the gripping image that will lead me to future research into Bernat Klein’s legacy in her description of her father’s Colour Box. This was a collection of hundreds of scraps and samples: ‘tiny twists of yarn, snippets of paper, dimples of wool and fingernails of cloth he’d collected for reference purposes. Whereas the great Victorian naturalists travelled the world collecting beetles and butterflies, Beri collected colours’. And as she explains, this was not colour in the abstract, nor even trapped within the more uniform slick of paint, but instead as glowing from within hundreds of discrete textured material objects, snatched out of the fleeting world of textile labour and thought, ready to inform new weave combinations. For me, that offers the first thread into the labyrinth.

Bernat Klein Exhibition, V&A Dundee: Photography by Michael Wolchover

For my next project, I will follow that twisting thread to consider colour in textiles, through close observation of Klein's weave designs, as a three-dimensional highly material juxtaposition of yarn design, weave design and dye, informed by Anni Albers's On Weaving and her notion of weave as a 'pliable plane' —that is, an entity that is not exactly two-dimensional, and not quite three-dimensional either. This zone is already part of specialist fields of mathematical/ material science research and the development of technical textiles. While I am unable to follow these enquiries in depth, I can enter this labyrinth by thinking not so much about strength and structure but about the woven plane as an aesthetic dimension specific to weave.

Dr. Frances Robertson is an independent researcher, formerly Lecturer and Reader in Material Cultures of Drawing at Glasgow School of Art where she taught design history and theory. She researches practices of drawing and print with reference to the history of technology, visual communication, and the constructed environment, also histories of dress and textiles. Selected publications include: ‘Redrafting domestic life: women textile designers and new professional enterprises in early 1970s Britain’ Textile history (2024 forthcoming); ‘Power in the Landscape’ in Kjetil Fallan, ed. The Culture of Nature in the History of Design (2019); ‘Chapter 13: Photography and illustration’ inThe Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press Volume 3: Power, Popularization and Permeation, 1900-2017 edited by Martin Conboy and Adrian Bingham, eds Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press 2020; Print Culture: Technologies of the Printed Page from Steam Press to eBook (2013).